Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) scientists are figuring out how to pack more kernels onto a corn cob. One way to boost the productivity of a plant, they say, is to redirect some of its resources away from maintaining an overprepared immune system and into enhanced seed production. Now, a team led by CSHL Professor David Jackson has found a gene that could help them tweak that balance.

To flourish in the wild, plants must be constantly on guard. With an unpredictable array of bacteria, fungi, and viruses lurking in the soil and air, a plant must maintain a robust immune system that is ready to counter any attack. This vigilance comes at a cost: Energy spent on pathogen defense cannot be used to grow taller or produce seeds. But the trade-off is crucial.

For crop plants, however, the situation is different. Corn growing in a farmer’s carefully tended field faces fewer threats than the same plant might encounter on an untamed prairie. In this controlled environment, plants could probably ease up on their anti-pathogen protections—but getting them to do so will require some genetic tinkering.

“If we can convince the plants that they don’t have to spend a lot of energy on defense, they can put more energy into making seeds,” Jackson says.

In work reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jackson and his team have identified a gene in corn that contributes to both the plant’s development and to the control of its immune system. Manipulating this gene, they say, could be a way to increase crop yields by reprogramming how a plant balances its investments in growth and defense.

Corn plants cannot survive without the gene, which is called Gß (pronounced GEE beta) and encodes part of an essential signaling complex. Seedlings engineered to lack Gß quickly turn brown and die, which postdoctoral fellows Qingyu Wu and Fang Xu determined was because the plant needs the gene to keep its immune system in check. Without it, an overactive immune system attacks the plant’s own cells.

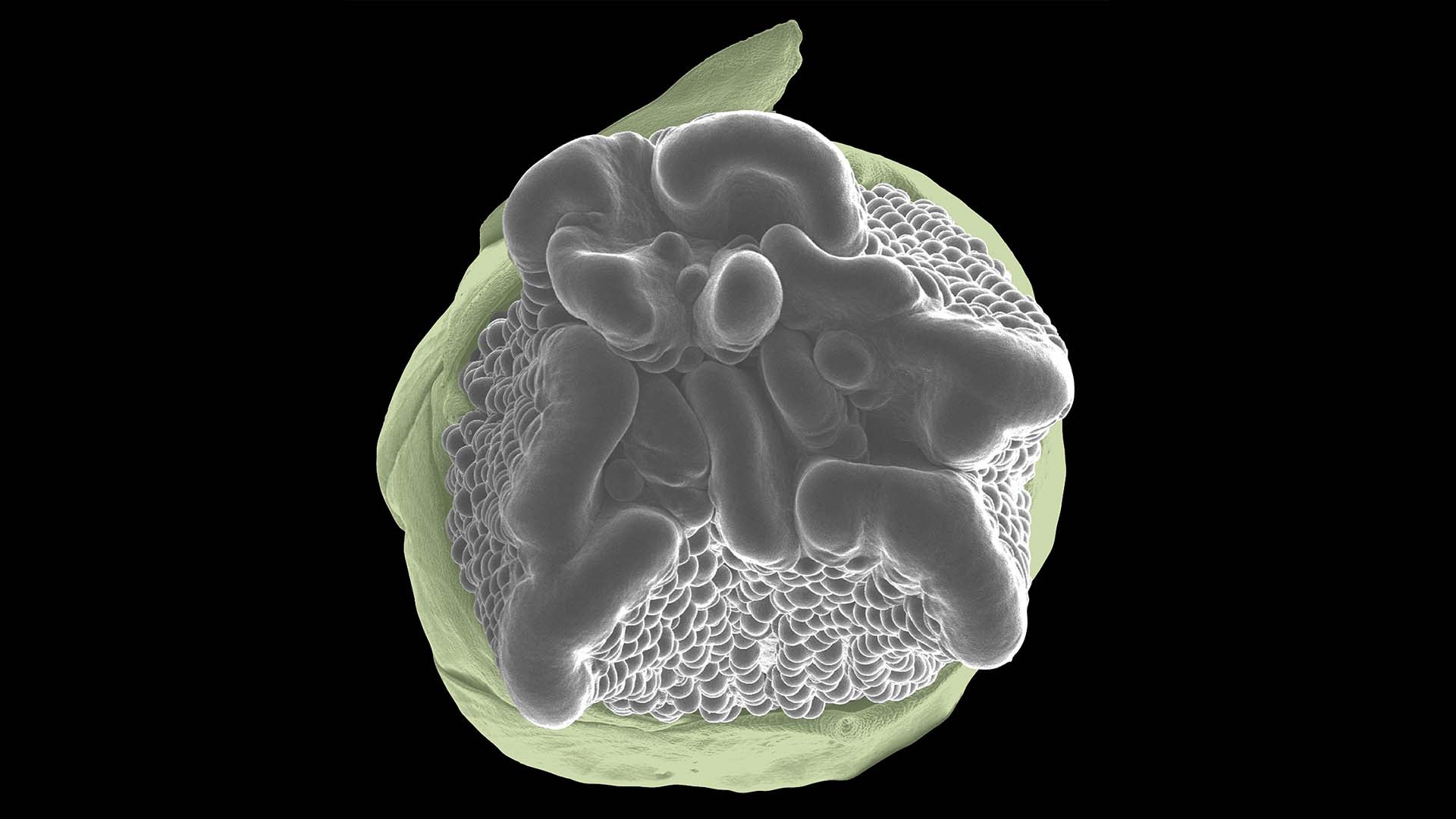

By experimenting with dozens of genetically diverse lines of corn, Wu and Xu found that within the right genetic context, plants can grow without Gß. By studying these plants, they discovered that Gß also impacts the size of a plant’s meristems, reservoirs of stem cells from which new growth originates. What’s more, the team linked naturally occurring variations in the Gß gene to the production of corn ears with unusually abundant kernels.

Jackson says his team’s findings indicate not only that Gß is involved in both growth and immunity, but that it likely mediates crosstalk between the cellular pathways that control these competing functions. The researchers are already digging deeper into those interactions, with the hope that they will be key to developing higher-yield crops.

Written by: Jennifer Michalowski, Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

This research was funded by the US Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture and the NSF.

Citation

Wu, Q. et al, “The maize heterotrimeric G protein β subunit controls shoot meristem development and immune responses” was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on December 18, 2019.

Principal Investigator

David Jackson

Professor

Ph.D., University of East Anglia, 1991