When the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern,” the world turned to science for help. Although modern research is fast, publishing findings in traditional peer-reviewed journals can take months. Luckily, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) had the vital infrastructure in place for scientists to communicate with each other quickly: the preprint servers bioRxiv and medRxiv.

Before the pandemic, scientists used preprints to seek feedback before submitting their work for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

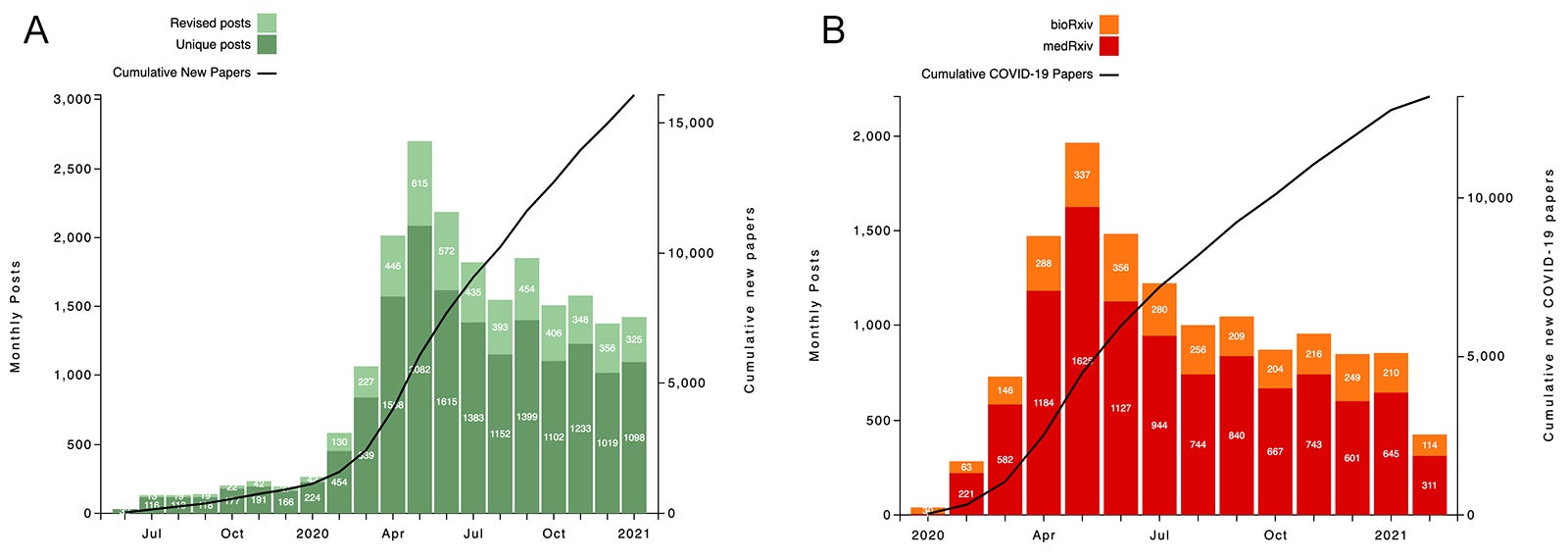

In January 2020, when medRxiv was only 7 months old, the servers started receiving coronavirus preprints. These were collected quickly to form the scientific community’s COVID-19 research communications hub, which 13 months later contained over 13,000 manuscripts. Researchers exchange data in almost real-time without having to wait for traditional peer-review. Preprints provided first accounts of many important insights: advances in the understanding of the virus’s biology and its effects on the human body, the science behind the pandemic’s spread, the development of diagnostic tests, therapeutic interventions (such as the RECOVERY clinical trial from the University of Oxford that revealed the value of a steroid treatment, dexamethasone), demonstrations that the medication hydroxychloroquine was not effective, and vaccine development. More recently, researchers started posting information on new viral variants and vaccine efficacy. COVID-19 preprints are still being added at a rate of about 850 per month.

John R. Inglis, executive director of the CSHL Press and a co-founder of both bioRxiv and medRxiv, says:

“A preprint server is made for this moment of urgency, of international concern, where the lessons learned by research and clinical communities in one geography need to be shared with people in other geographies so that they can figure out whether the same lessons apply. The entire scholarly publishing ecosystem has stepped up to the challenge of COVID-19, and journals are pushing papers through as fast as they can, but the journal publishing infrastructure is not built for this. The promise of the wholesale adoption of preprints is that this is such a different model: distribute first, peer review, and assess afterwards.”

On January 21, 2021, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and chief medical advisor to President Joe Biden, spoke about the emergence of new viral variants and the efficacy of vaccines in his first press briefing for the Biden Administration: “We have this new phenomenon where people get data and they put it into a preprint server where it hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, but you have to pay attention to it because it gives you good information quickly.” All that work was visible to anyone who cared to look. Inglis says:

“If there is any benefit to be gained from the past year, it might be that the public has slowly begun to see that science isn’t the way that they thought it was. It is a whole lot of highly principled and well-intentioned people wrestling with big problems and sharing their results, recognizing that it is an imperfect process, but collectively, it can be made more perfect.”

Inglis says, “the medical community has become aware of, and hopefully has begun to learn about, the value of this mode of communication.” As more researchers become accustomed to using preprints and journalists learn how to report on them, Inglis hopes the world will be better positioned to fight the next health emergency.

Written by: Jasmine Lee, Content Developer/Communicator | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8845