In the summer of 1905, on a small patch of land next to what is now the Carnegie Building at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a 31-year old scientist named George Shull began to grow maize, or corn, in a series of experiments that would change the face of modern agriculture. In 2010, CSHL scientists made two fundamental discoveries that continue the legacy at the Laboratory that began with Shull to improve the world’s food supply. Read the full story in the Winter 2010 edition of the Harbor Transcript.

At CSHL, the quest to improve food production began in the early 1900s with George Shull--the son of an Ohio farmer and his horticulturist wife--who turned his childhood interest in plants into a career as a botanist. Credits: Archives@CSHL

At CSHL, the quest to improve food production began in the early 1900s with George Shull--the son of an Ohio farmer and his horticulturist wife--who turned his childhood interest in plants into a career as a botanist. Credits: Archives@CSHL In 1904, Shull arrived at the Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor with ambitious plans: to generate experimental support for the ideas of Charles Darwin. Credits: Archives@CSHL

In 1904, Shull arrived at the Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor with ambitious plans: to generate experimental support for the ideas of Charles Darwin. Credits: Archives@CSHL A year later, Shull began to work on corn (maize), turning the land adjoining the Carnegie Building, which now houses CSHL's library and archives, into a cornfield. Credits: Archives@CSHL

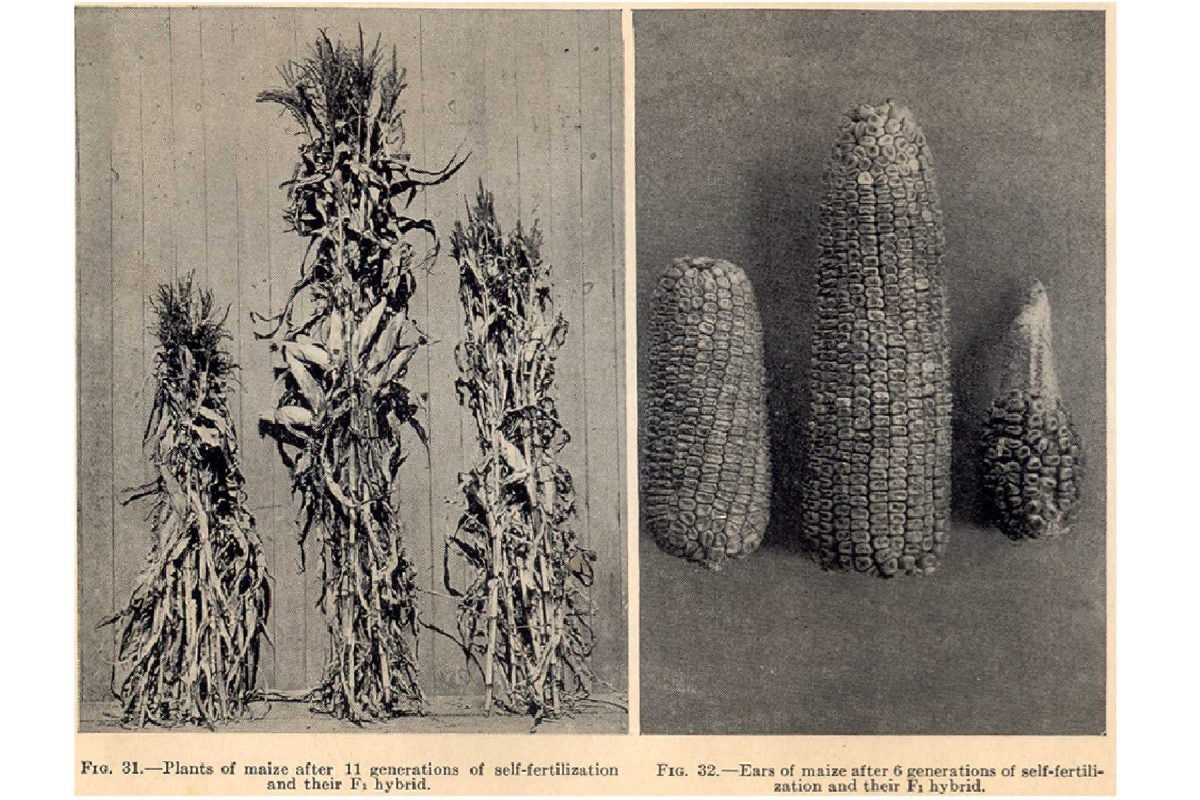

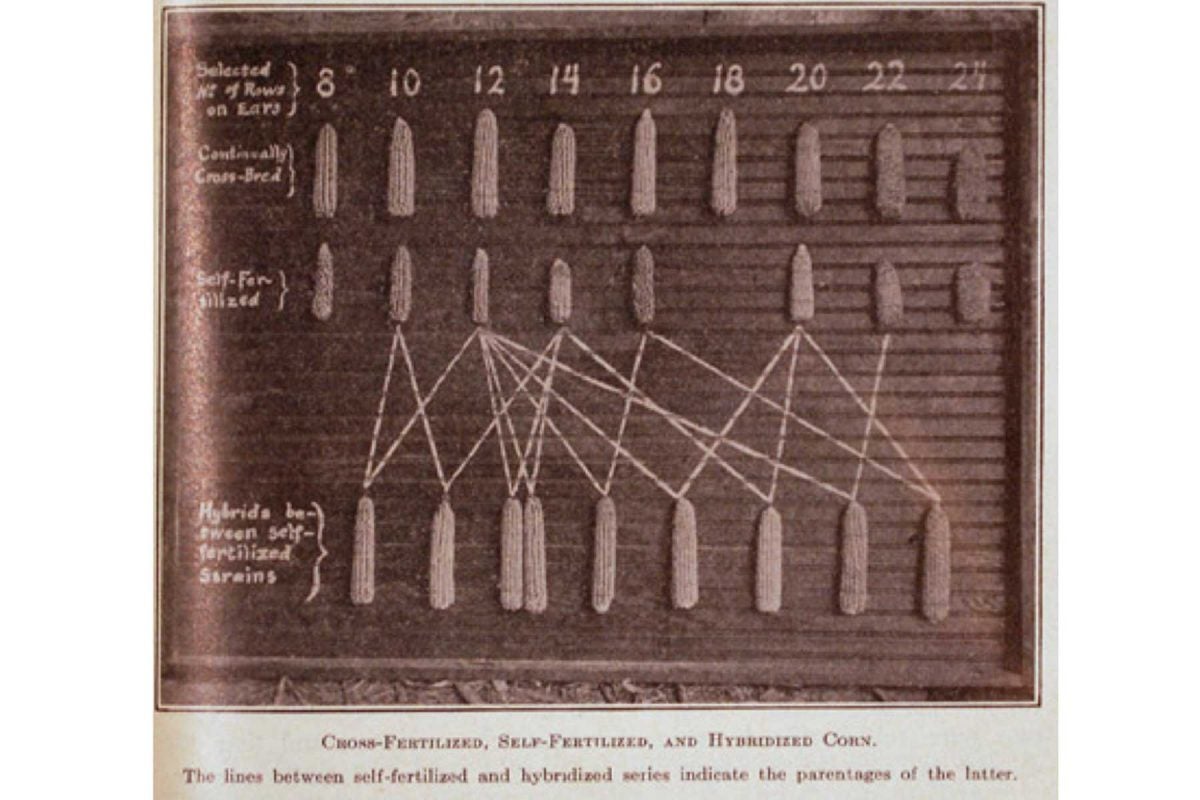

A year later, Shull began to work on corn (maize), turning the land adjoining the Carnegie Building, which now houses CSHL's library and archives, into a cornfield. Credits: Archives@CSHL Shull discovered that self-pollinating a corn plant for generations resulted in pure-bred lines that were less vigorous and productive in each generation. But crossing these lines resulted in hybrids (F1) that spectacularly outperformed their parents in growth and yield.

Shull discovered that self-pollinating a corn plant for generations resulted in pure-bred lines that were less vigorous and productive in each generation. But crossing these lines resulted in hybrids (F1) that spectacularly outperformed their parents in growth and yield. Shull's crosses revealed the phenomenon of hybrid vigor, which proved to be a successful strategy for increasing crop yields and one of the most important breeding principles ever uncovered in agriculture.

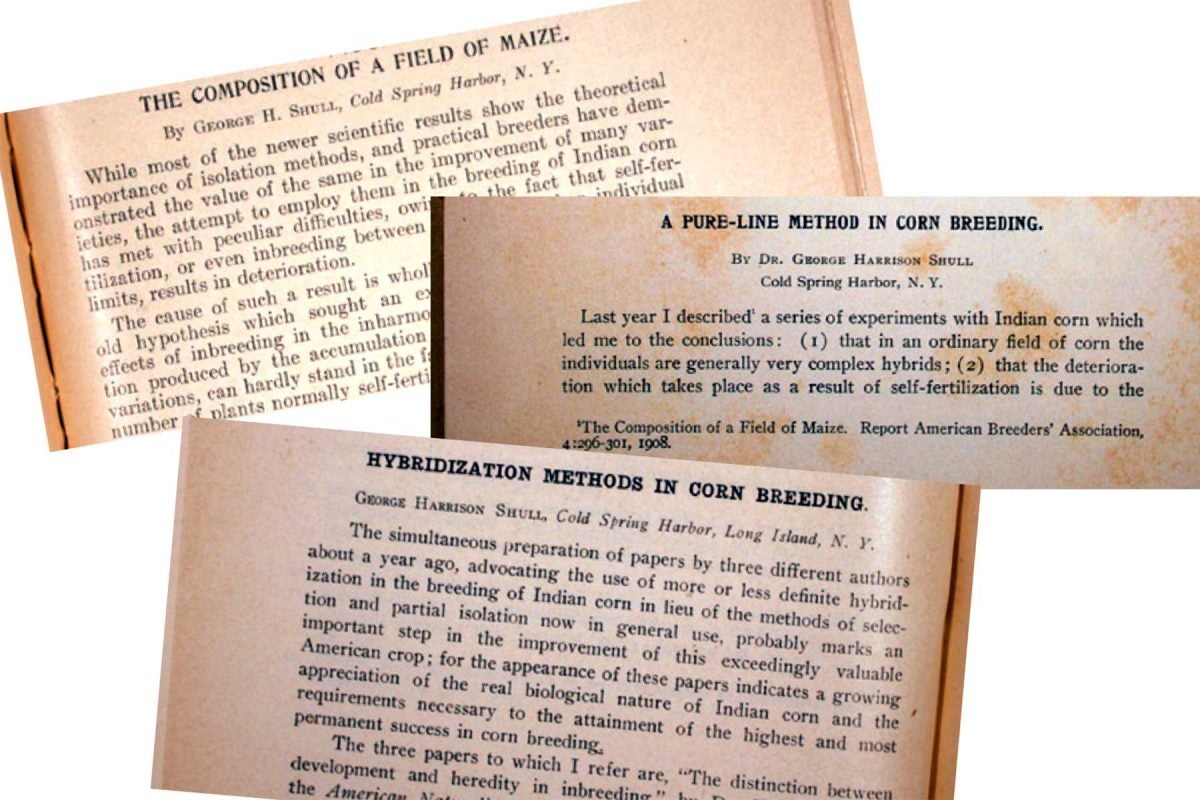

Shull's crosses revealed the phenomenon of hybrid vigor, which proved to be a successful strategy for increasing crop yields and one of the most important breeding principles ever uncovered in agriculture. Three papers published between 1908 and 1910 described Shull's revolutionary discoveries.

Three papers published between 1908 and 1910 described Shull's revolutionary discoveries. More than a century later, scientists are still mostly in the dark about the genes and mechanisms that drive hybrid vigor, or heterosis--a puzzle that CSHL Assistant Professor Zachary Lippman is working hard to solve.

More than a century later, scientists are still mostly in the dark about the genes and mechanisms that drive hybrid vigor, or heterosis--a puzzle that CSHL Assistant Professor Zachary Lippman is working hard to solve. As a postdoctoral researcher at Israel's Hebrew University, Lippman worked with Professor Dani Zamir to hunt for heterosis genes in tomato, a good stand-in for many crop species. Credit: Lippman@CSHL

As a postdoctoral researcher at Israel's Hebrew University, Lippman worked with Professor Dani Zamir to hunt for heterosis genes in tomato, a good stand-in for many crop species. Credit: Lippman@CSHL The team found a promising lead by crossing plants chosen from a 'mutant library' of 5,000 tomato plants, each of which has a single mutation in a single gene that causes defects in various aspects of tomato growth. Credit: Lippman@CSHL

The team found a promising lead by crossing plants chosen from a 'mutant library' of 5,000 tomato plants, each of which has a single mutation in a single gene that causes defects in various aspects of tomato growth. Credit: Lippman@CSHL The lead turned out to be a gene called single flower truss (sft), which controls when and how plants make flowers (which in turn produce fruit). Credit: Lippman@CSHL

The lead turned out to be a gene called single flower truss (sft), which controls when and how plants make flowers (which in turn produce fruit). Credit: Lippman@CSHL When expressed in tomatoes, this single gene increases yields by a dramatic 60% in hybrids (middle) that have one normal copy and one mutated copy of the gene. Credit: Lippman@CSHL

When expressed in tomatoes, this single gene increases yields by a dramatic 60% in hybrids (middle) that have one normal copy and one mutated copy of the gene. Credit: Lippman@CSHL Lippman confirmed sft's vigor-boosting power in different tomato varieties. Credit: Renna@CSHL

Lippman confirmed sft's vigor-boosting power in different tomato varieties. Credit: Renna@CSHL He also confirmed it in plants grown in different climates and soil conditions, such as at CSHL's own Uplands Farm (above) and at the Cornell Horticultural Station at Riverhead, NY.

He also confirmed it in plants grown in different climates and soil conditions, such as at CSHL's own Uplands Farm (above) and at the Cornell Horticultural Station at Riverhead, NY. Lippman's discovery, which has profound implications for the billion-dollar tomato industry, was featured widely in the popular press, including this feature in The New York Times.

Lippman's discovery, which has profound implications for the billion-dollar tomato industry, was featured widely in the popular press, including this feature in The New York Times. Lippman is trying to identify the genetic factors in tomato plants that control branching and specify the number of flowers (which in turn produce fruits) on structures called inflorescences. Credit: Renna@CSHL

Lippman is trying to identify the genetic factors in tomato plants that control branching and specify the number of flowers (which in turn produce fruits) on structures called inflorescences. Credit: Renna@CSHL He and CSHL Professor David Jackson (center) have teamed up to investigate genes and mechanisms that can drive yield in other major crop species such as corn. Credit: Michael Englert

He and CSHL Professor David Jackson (center) have teamed up to investigate genes and mechanisms that can drive yield in other major crop species such as corn. Credit: Michael Englert The ultimate goal is to make a high-yield hybrid without the labor-intensive crossing of plant lines. To achieve this, CSHL Professor Rob Martienssen is investigating a phenomenon called apomixis.

The ultimate goal is to make a high-yield hybrid without the labor-intensive crossing of plant lines. To achieve this, CSHL Professor Rob Martienssen is investigating a phenomenon called apomixis. Martienssen was trained by CSHL geneticist Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize for her discovery of mobile bits of DNA--'jumping genes'--60 years ago. Credits: Archives@CSHL

Martienssen was trained by CSHL geneticist Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize for her discovery of mobile bits of DNA--'jumping genes'--60 years ago. Credits: Archives@CSHL Apomixis, which occurs in more than 350 plant families, allows plants to reproduce asexually and thereby make exact genetic replicas of themselves.

Apomixis, which occurs in more than 350 plant families, allows plants to reproduce asexually and thereby make exact genetic replicas of themselves. Crops such as corn are sexual reproducers, so desirable traits such as high yield can be lost during their reproduction. Forcing them to reproduce asexually can prevent this loss. Credit: Renna@CSHL

Crops such as corn are sexual reproducers, so desirable traits such as high yield can be lost during their reproduction. Forcing them to reproduce asexually can prevent this loss. Credit: Renna@CSHL Early in 2010, in collaboration with a research team from Mexico led by Jean-Philippe Vielle-Calzada, Martienssen's group forced the sexually reproducing Arabidopsis thaliana, the mustard plant, to the brink of asexual reproduction.

Early in 2010, in collaboration with a research team from Mexico led by Jean-Philippe Vielle-Calzada, Martienssen's group forced the sexually reproducing Arabidopsis thaliana, the mustard plant, to the brink of asexual reproduction. When the researchers shut down a gene called Argonaute 9 in the mustard plant, they observed signs of asexual reproduction in the plant's reproductive organs (arrows).

When the researchers shut down a gene called Argonaute 9 in the mustard plant, they observed signs of asexual reproduction in the plant's reproductive organs (arrows). The next step is to refine the process of obtaining viable asexual seeds and apply it to crops such as corn. Next summer, CSHL plant geneticists hope to harvest an apomictic corn plant at CSHL's Uplands Farm. Credit: Renna@CSHL

The next step is to refine the process of obtaining viable asexual seeds and apply it to crops such as corn. Next summer, CSHL plant geneticists hope to harvest an apomictic corn plant at CSHL's Uplands Farm. Credit: Renna@CSHL

Written by: Communications Department | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Stay informed

Sign up for our newsletter to get the latest discoveries, upcoming events, videos, podcasts, and a news roundup delivered straight to your inbox every month.