Cold Spring Harbor, NY — One of the most hopeful discoveries of modern neuroscience is firm proof that the human brain is not static following birth. Rather, it is continually renewing itself, via a process called postnatal neurogenesis—literally, the birth of new neurons. It begins not long after birth and continues into old age. There is some evidence that when people respond to depression treatment, be it a pill or talk therapy, it has something to do with the wiring up of new neurons.

For reasons still not understood, only two parts of the human brain receive replenishments of neurons postnatally. One is a section of a tiny seahorse-shaped structure called the hippocampus, central in memory and learning. The other is the olfactory bulb, located in a small patch of tissue inside the nose, which receives signals from the environment and helps make them intelligible so they can serve as a basis for action—for instance, to recoil from curdled milk or veer from a stinking skunk.

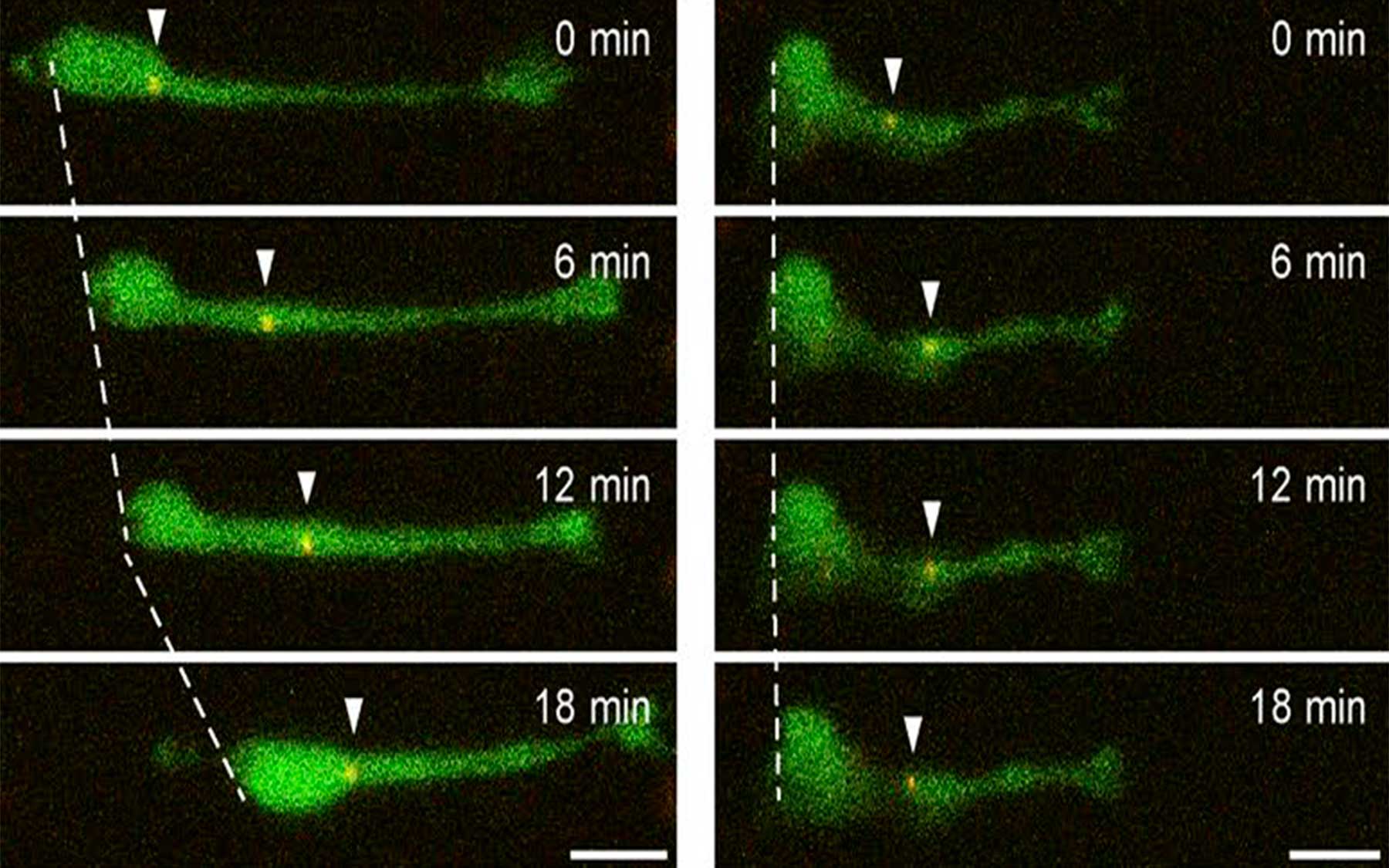

Neurons in the making—called neuroblasts—migrate from deep within the mouse brain through a tunnel to positions in the olfactory bulb. How they do so—seeming to creep and crawl like inchworms—is the subject of new findings from the lab of Professor Linda Van Aelst of CSHL.

This week in the Journal of Cell Biology, Professor Linda Van Aelst and colleagues at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) describe for the first time (in mice) how baby neurons—precursors called neuroblasts, generated from a permanent pocket of stem cells in a brain area called the V-SVZ—make an incredible journey from their place of birth through a special tunnel called the RMS to their target destination in the olfactory bulb. They travel as far as 8 mm, “a huge distance, when you consider how tiny the mouse brain is,” Van Aelst says.

The journey is made possible by two forces, one pulling from the front, the other pushing from behind. A single protein called DOCK7 helps to orchestrate these two steps. Ahead of the newborn neuron’s soma, or cell body, is a threadlike projection called a process. It stretches forward through the tunnel, guided by various signals. At the same time, the cell body, lagging behind, is powered forward by the activation of tiny molecular motors that push it from the rear. Multiple cells migrate together, one virtually on top of another, somewhat in the manner of a group of tiny worms inching forward by morphing the shape of their bodies.

Written by: Peter Tarr, Senior Science Writer | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455

Funding

National Institutes of Health; Uehara Memorial Foundation

Citation

Nakamuta S et al, “Dual role for DOCK7 in tangential migration of interneuron precursors in the postnatal forebrain” appears in Journal of Cell Biology the week of October 31, 2017

Principal Investigator

Linda Van Aelst

Professor

Harold and Florence & Ethel McNeill Professor of Cancer Research

Cancer Center Program Co-Leader

Ph.D., Catholic University of Leuven, 1991