Sarcoma is a rare and deadly cancer born of bones, muscles, or connective tissue. Striking children and young adults, it was studied by only a handful of disconnected researchers. But that changed in 2014, when the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Cancer Center launched its Sarcoma Initiative. The Laboratory helped organize the field, develop a roadmap to a cure, and build the most active research program in the world focused on sarcoma research.

After decades with little progress, CSHL researchers took only five years to find new drug targets, paving the way for new treatments. And the story of this unique research effort began not in a lab, but with three Long Island families.

Three local foundations dedicated to curing sarcoma

TJ was 31 years old when he was diagnosed with sarcoma. While he was undergoing treatment, he and his friends started a foundation, The Friends of TJ. After TJ died in 2012, his parents and friends were determined to find a cure for the disease.

In 2007, CSHL employee Philip Renna lost his daughter Christina to rhabdomyosarcoma. The Renna family established the Christina Renna Foundation (CRF) to support research on childhood cancers.

Michelle was newly married to Paul Paternoster when she was diagnosed with sarcoma. After she died in 2013 at the age of 34, Paul founded the Michelle Paternoster Foundation, dedicated to sarcoma research and to helping kids with cancer.

By 2014, all three foundations were looking for a researcher to study sarcoma. But who? Where? Was there a scientist at the CSHL Cancer Center to do it? Setting up a new research program requires both funders and the institution to commit considerable resources. In general, the rarer a disease, the less investment goes into fighting it. Sarcoma is a very rare disease and thus had little investment.

CSHL President and CEO Bruce Stillman needed to learn what was known about sarcoma biology to see if the Laboratory had the tools to help. He would not accept the three foundations’ support if he didn’t think his institution could make a difference. So he decided to convene the world’s first stakeholder meeting on sarcoma research.

The first-ever meeting of the international sarcoma research community

In May of 2014, Stillman invited sarcoma clinicians and researchers from around the world to the CSHL Banbury Conference Center to present what was known about the disease. The three foundations supported the meeting and also attended as stakeholders.

Tom Arcati, TJ Arcati’s father, asked the clinicians and researchers when they held their last sarcoma conference. “They looked down kind of glumly and said, ‘Never. This is the first one.’ And I was literally blown away.” Renna observed, “It was the first time somebody who was treating the child actually got to sit with a researcher who was working on that cancer.”

The conference attendees agreed that a sarcoma cell must have a signaling problem. Since the cell couldn’t fully become (differentiate into) a muscle cell or an immune cell, the cascade of signals that would tell it what to become was broken. Stillman had his interesting biological question: what broke along the differentiation-signaling pathway?

Sarcoma Initiative launched at CSHL in 2014

After the Banbury meeting, attendees worked together to publish a paper describing what was known about sarcomas, focusing the field on a few promising research ideas, and laying out a roadmap to a sarcoma cure:

Phase 1. Figure out a sarcoma’s missed differentiation signals and other basic biology;

Phase 2. Narrow down the genes involved to a few targets that could be manipulated through drugs;

Phase 3. Work with a drug company to repurpose an existing drug or develop a new one;

Phase 4. Go into clinical trials.

Stillman invited an early career researcher and pediatric oncologist at CSHL, Chris Vakoc, to consider the problem. Vakoc used CRISPR to edit genes and screen for ones involved in leukemia. He could then quickly select domains of the cancer-causing genes as possible drug targets.

“Bruce (Stillman) saw some of the technology we were developing for drug target discovery in leukemia,” recalled Vakoc. “And he kind of saw the opportunity before I did. He suggested: could we apply that technology to sarcoma? So once he presented me with this opportunity, it became very compelling. It was something I had to work on.”

Later that year, CSHL launched its sarcoma research program with Vakoc in the lead. The three local foundations committed to funding the program and later were joined by other local funders. Together, as of September 2021, they have donated $1.2 million.

The stories behind the three foundations

The Friends of TJ Foundation

TJ Arcati was an anesthesiologist, married, with a young family. He died of sarcoma at the age of 34. His parents, Tom and Nancy Arcati, and his friends continue the work of the foundation he started and advise other sarcoma families. Nancy says: “I realize some people don’t want to be subjected to sad things. They want to be more private, but we decided making a difference is more important.”

The Christina Renna Foundation

Christina’s high school running days were curtailed when she was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma at fourteen. Christina said, “When you hear the word cancer for the first time, your life takes on new meaning. All the things that you thought were important turn out not to be. The things you take for granted every day like eating, running, school, friends, and even your hair, now become even more special.” Christina passed away at the age of sixteen and her family established the foundation in her name the following year.

The Michelle Paternoster Foundation

Michelle’s husband Paul Paternoster remembers that “she was always bright, optimistic, happy, funny.” Once, at the sarcoma clinic, they saw a young patient wearing a Mets jersey. Paul and Michelle had four tickets for the Mets’ opening day later that afternoon. They looked at each other and wordlessly handed over their tickets to that child and his family. The foundation established in her name invests in the things she cared about most.

Rapid progress: Hoping for a cure soon

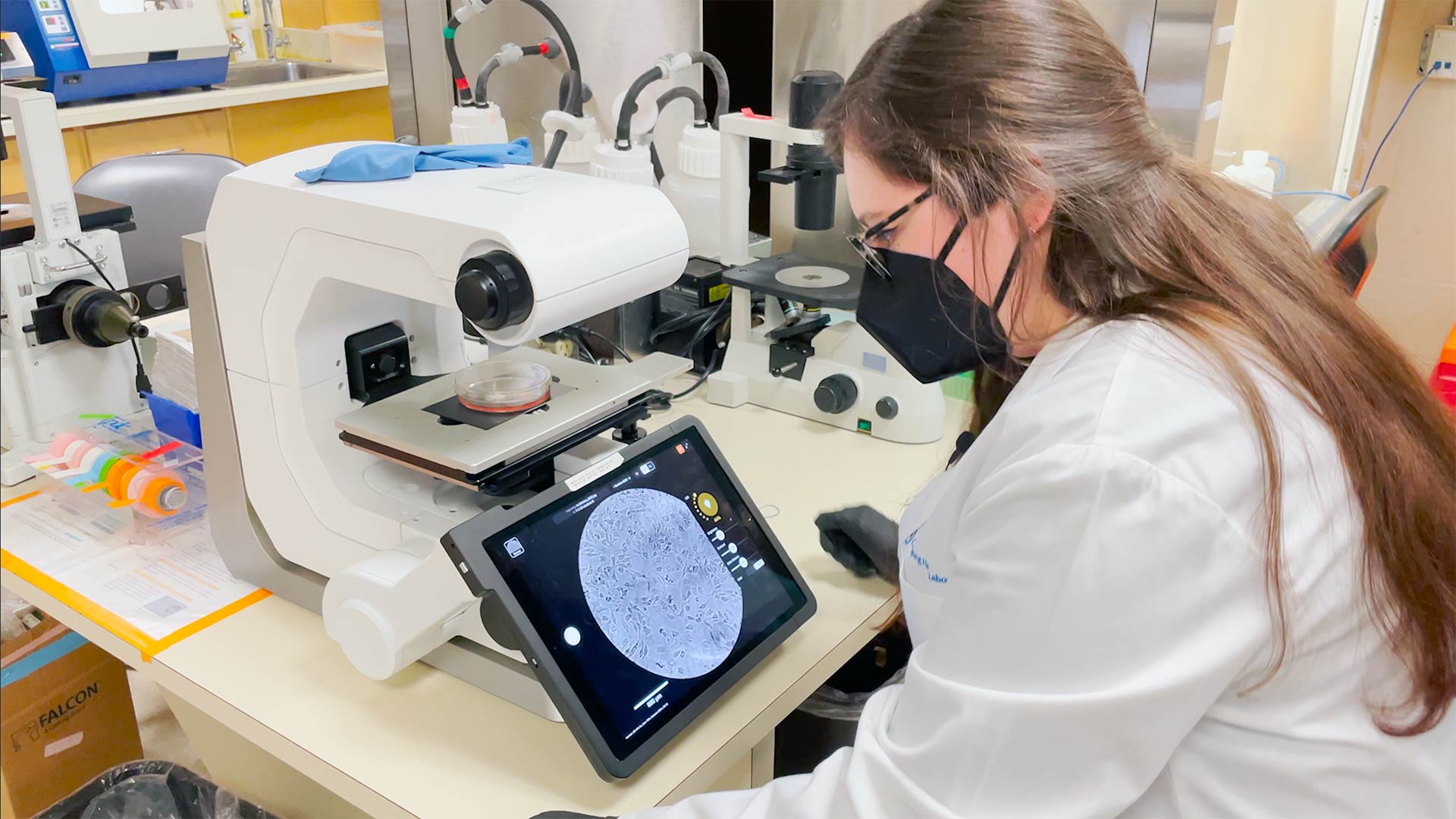

CSHL turned out to be an ideal place to work on sarcomas. With its history of state-of-the-art genetics and genomics research facilities, the Lab’s Cancer Center also recently invested in a large facility that can culture organoids—small balls of cells grown from patient biopsies. The Laboratory’s resources include cutting-edge imaging machines to visualize tissues, and a cadre of experts in the Simons Center for Quantitative Biology to analyze data.

By 2019 Vakoc had completed the first two of the four-phase plan. “We have identified four novel therapeutic targets in rhabdomyosarcoma (which starts in skeletal muscles) and in synovial sarcoma (found in connective tissue),” Vakoc said that year. “These discoveries represent an exciting milestone in this project. Our ongoing efforts will take these novel targets to the next stage of drug development with therapeutic intent.”

Renna attributes the Laboratory’s rapid progress on a sarcoma cure to a fortuitous convergence of all the right people, facilities, and ideas assembled in one place: “There’s a lot of serendipity here. All the players were in place. The money matters, but so does the science. It could have taken thirty years to move from basic research into a clinical application. Chris (Vakoc) took only five years to study the basic science, identify multiple targets, and figure out how to attack those targets. To see this result in my own lifetime, that is amazing, absolutely amazing.”

Written by: Eliene Augenbraun, Creative Director | publicaffairs@cshl.edu | 516-367-8455