Autism genetics expert Ivan Iossifov breaks down recent research that sheds light on how unaffected parents can pass autism onto their child.

Parents with no history of autism in their families have a child who is diagnosed with the disorder. It’s a common and upsetting story.A quick Google search for “autism causes” is all it takes to learn that scientists believe the disorder has a strong genetic component. So if there’s no genetic history in the family, where does a child’s autism come from?

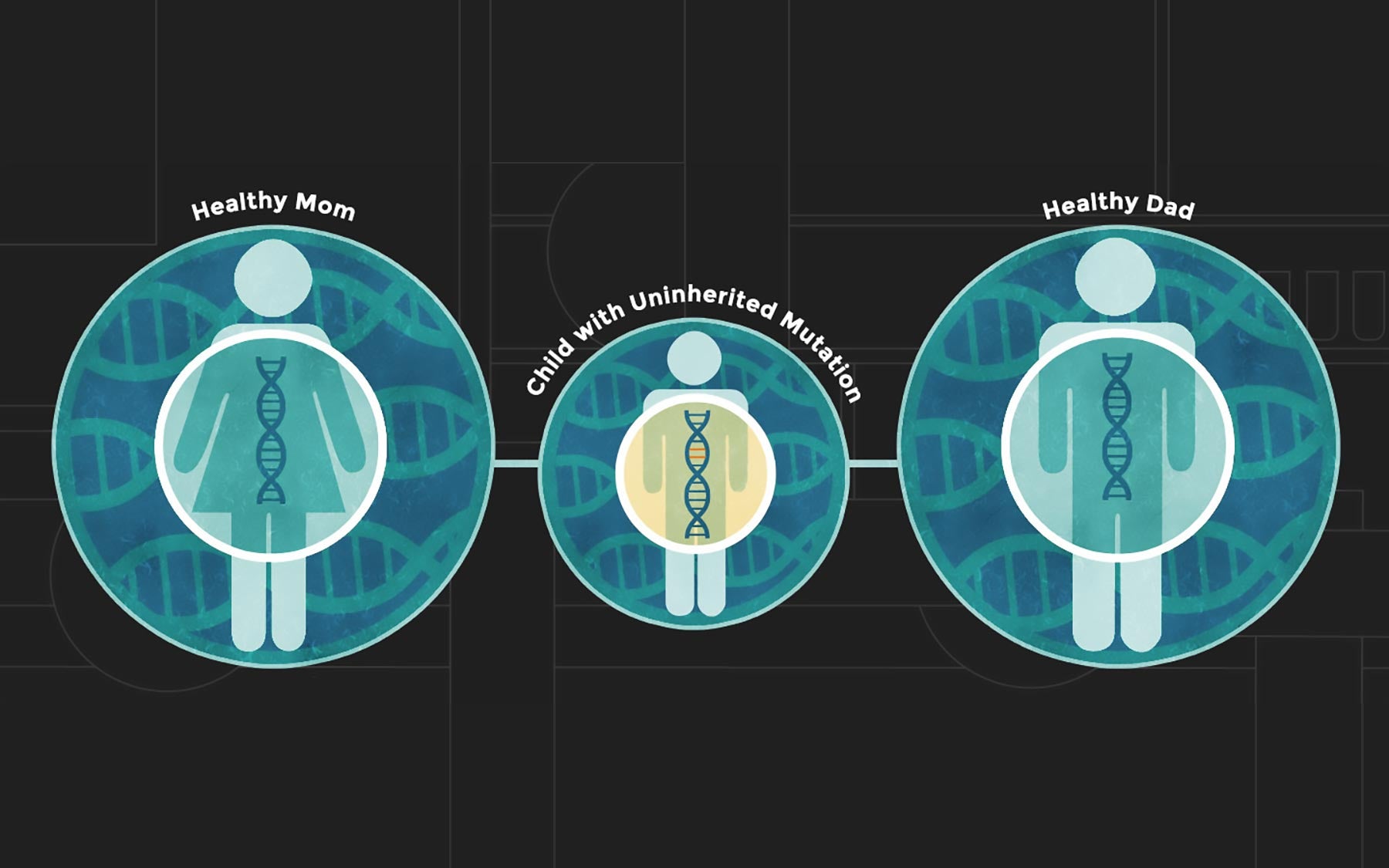

A key fact has come to light within the last couple of years: many autism-causing genetic mutations are “spontaneous.” They occur in the affected child, but in neither parent. Mutations in this category “are not directly inherited from the parents,” explains Assistant Professor Ivan Iossifov, one of several CSHL scientists who has pioneered the study of the role of spontaneous mutations in autism causation.

A child’s genome is a patchwork stitched together from the genetic “cloth” contained in the mother’s egg and father’s sperm. In theory, that means that children are cut from exactly the same cloth as their parents. But in reality, there are virtually always small “factory defects” in that cloth—mutations that spontaneously arise during the sperm or egg’s creation.

Spontaneous mutations cause as much as half of all autism in situations in which only one child in the family has autism. This and other analysis comes from a study Iossifov published in 2015. He and his team looked at about 2,500 families with a single affected child and investigated the causal link to spontaneous mutations.

Professor Michael Wigler explains the genetic factors at play in his “unified theory of autism”

As Iossifov says, all of us have such mutations, and usually they have no effect at all. Humans normally have two copies of every gene, even though only one working copy typically necessary for proper functioning.

“We have two copies of most genes for a reason—it’s kind of a buffer,” says Iossifov.

This buffer protects us from spontaneous mutations in many of our genes. Iossifov and CSHL collaborator Michael Wigler theorize, however, that autism “risk genes” are particularly vulnerable to mutations. One reason is that for such genes, a person must have two working copies to function normally. As a result, a spontaneous mutation in one of these autism risk genes tends to have devastating effects.

Other major potential explanations for sporadic autism are also actively being studied, Iossifov notes, including other genetic causes and the role of factors in a child’s environment.

Read this next: What do autism “risk genes” do?

Note: For the sake of simplicity, this article uses the term ‘autism’ to refer to all autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). You can find out more about the distinction between autism and ASD here.