Miriam Rich, the recipient of CSHL’s 2017-18 Sydney Brenner Research Scholarship, is determined to show how the concept of “good genes” became disastrous in American history.

Good genes” sounds like something we should want. The idea is so appealing that the marketers of Sephora thought it would help entice you to pay $158 for a tiny bottle of their “Good Genes” skin product. Miriam Rich, the recipient of the CSHL Archive’s 2017-18 Sydney Brenner Research Scholarship in support of her doctoral research at Harvard, is determined to show how that concept became disastrous in American history.Eugenics was a movement that grew out of the idea of good genes, and countless appalling acts were committed in its name. The word itself is derived from the Greek eu, meaning “good,” and genos, which gave rise to the English word “gene.” The problem is, promoting “good genes” can all too easily turn into a crusade against “bad genes” and the people who carry them, Rich explains.

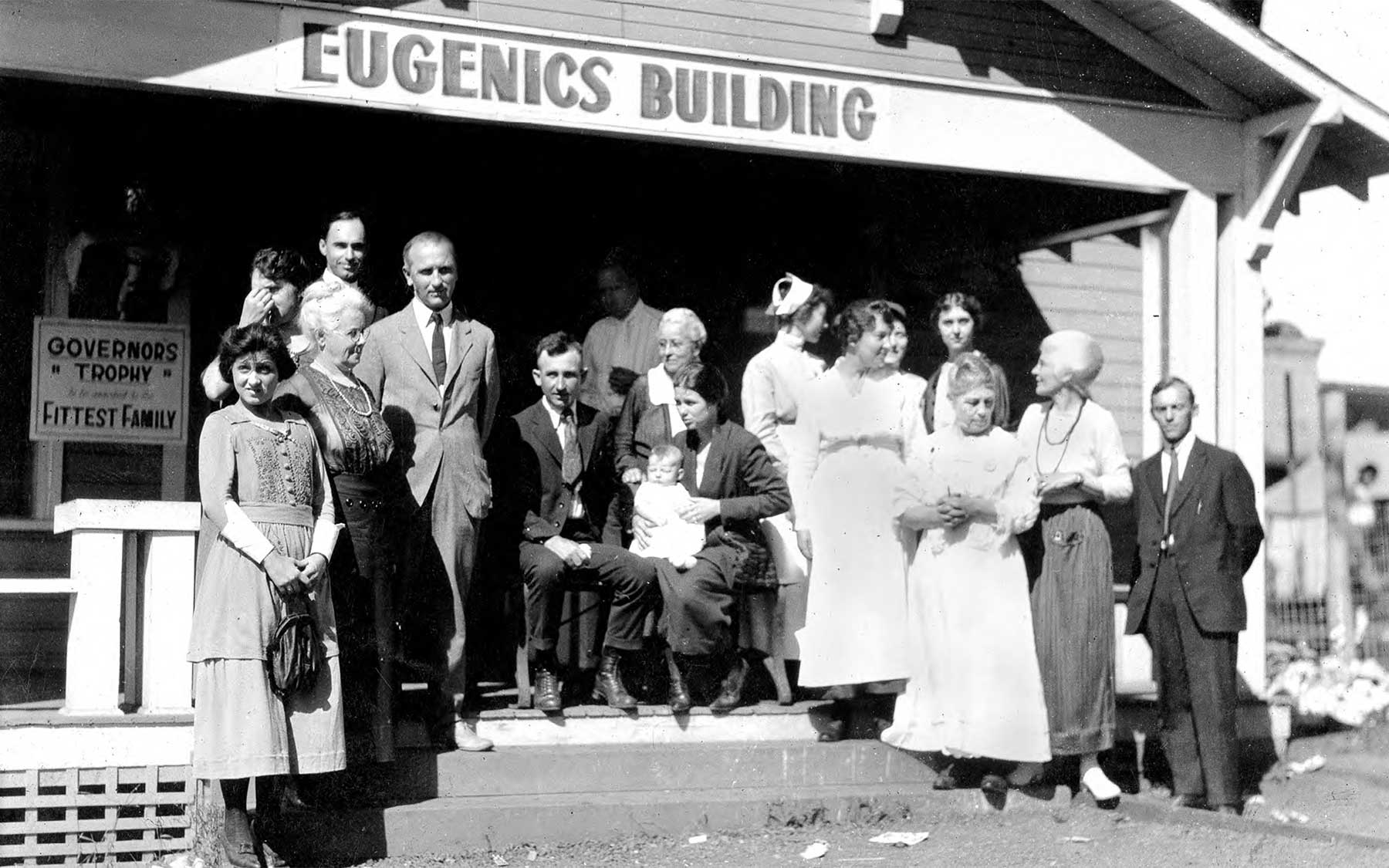

That’s what happened in the United States in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, when laws were passed that forced people considered to have bad genes to undergo operations that destroyed their ability to have children, among other horrors. Leaders of the American eugenics movement, however, described forced sterilization and related practices as “using science to achieve human improvement,” Rich says. This framing helped them win support for such policies from “many people, many more than can be explained as a fringe or an extremist group.”

As a historian of science and medicine, Rich looks to the social and political context of the time to understand how the ideas of the American eugenics movement, which are so repugnant in retrospect, became “very mainstream.” It’s easy to think that warning signs would be obvious, but a close look at history reveals that this is not necessarily the case. Rich strongly believes that “we have to have a really robust understanding of what eugenics was historically and what specifically we want to avoid recapitulating.”

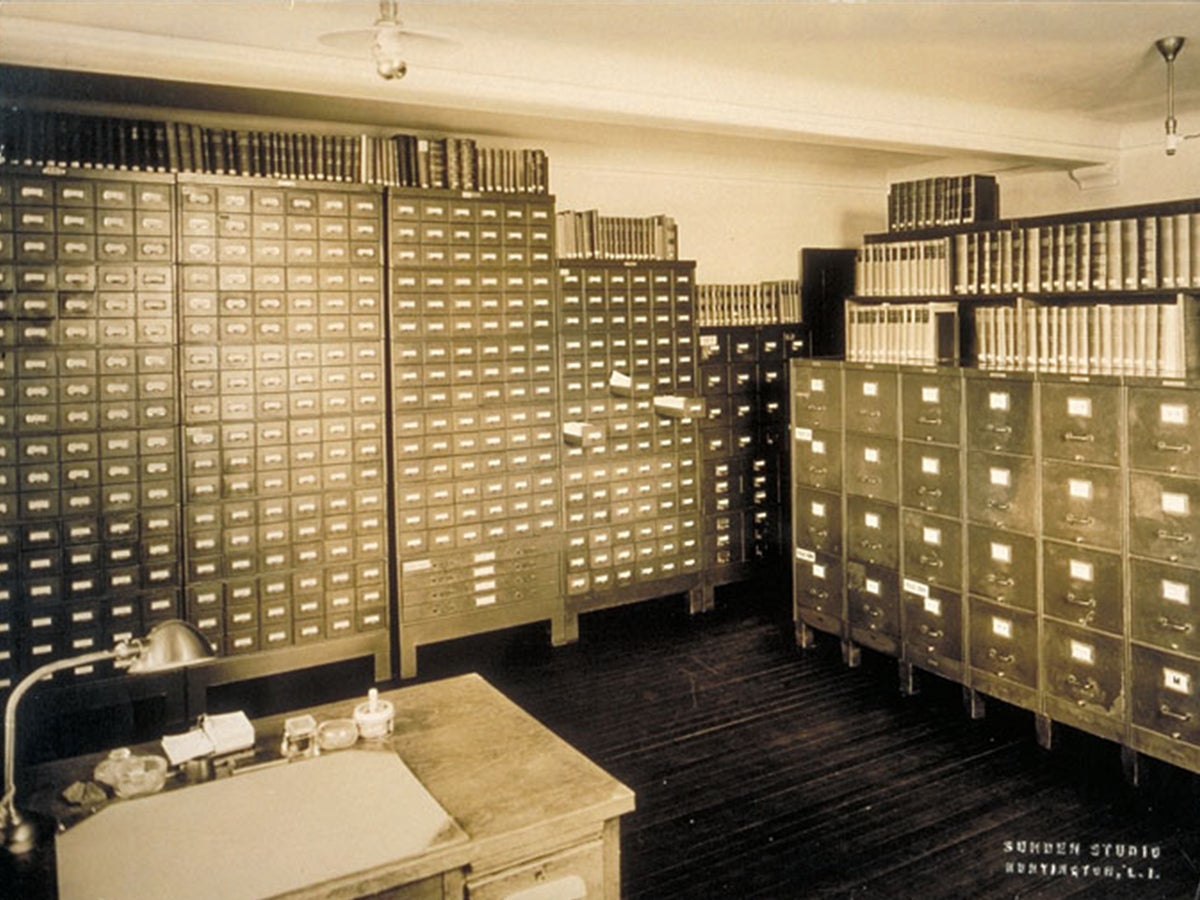

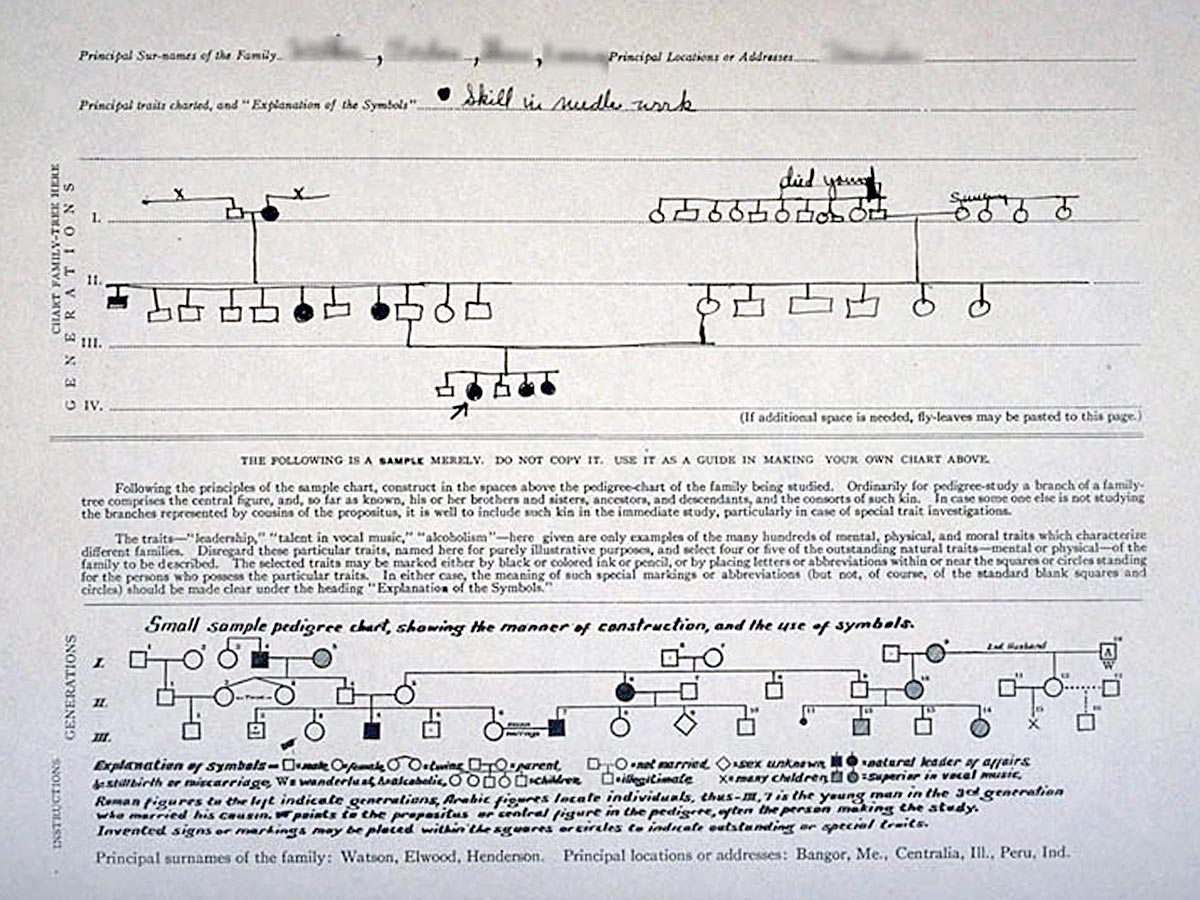

This mission led her Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), which was known as the Carnegie Institution of Washington back in the days of the American eugenics movement and was home to the Eugenics Record Office. That office held rows upon rows of filing cabinets full of family trees and other genetic data. Such documents helped create what Rich describes as “the veneer of quiet, almost dull scholarly legitimacy,” which bolstered eugenicists’ efforts.

It was indeed biologists who played a very prominent role in organizing the eugenics movement. Some intended for their science to be used in the persecution of marginalized groups. Others merely supported the broad idea of human improvement, but “failing to consider the specific social and political context allowed them to ignore that in practice, these eugenic interventions were reinforcing and exacerbating existing discrimination based on class, race, immigration status, disability,” says Rich.

Today, new technologies such as CRISPR genome editing are making it more important than ever to ensure that scientists, policymakers, and others take the ethical lessons from the history of eugenics into account. Few would argue against using CRISPR to fix “bad genes” that cause cancer, but where do we draw the line between “good” and “bad” genes?

Rich says that while she believes that ethical dangers exist “whenever topics deal with things that have social and political resonance,” that “doesn’t suggest that those topics shouldn’t be objects of scientific research.” But careful thought about those social and political implications is essential, she says, and history is an invaluable resource.

For that reason, documents from the Eugenics Record Office are still kept and made available at CSHL today, in the one of the many collections in the Archives and also online, in an extensive and widely used website to help the public understand what went wrong in the Eugenics Movement. “That’s such a great thing because it would be easy to think of this as a very shameful episode that the Laboratory would want to hide, forget, push away,” Rich says, adding, “Pretending it didn’t happen doesn’t do anything to learn from it.”

Watch ‘Eugenics: A Historical Perspective‘ public lecture.